By Jonah Ruddock

“We spend our lives learning many things, only to discover (again and again) that most of what we’ve learned is either wrong or irrelevant,” writes Chuck Klosterman in But What If We’re Wrong?, a book devoted to the idea that it’s foolhardy to be certain of… well, basically anything. Consider it, though: most of history consists of old ideas being overturned by new ones, and some of the things people faithfully believed in just decades ago are laughable today.

It’s highly unlikely that our current understanding of the world will be the final one. As Klosterman puts it, “We’re starting to behave as if we’ve reached the end of human knowledge. And while that notion is undoubtedly false, the sensation of certitude it generates is paralyzing.” He argues that we should accept the fact that we could be mistaken about some very fundamental things. For example, how can we be at all certain that we are not living in a simulation?

It’s generally agreed that a human mind has no way of knowing whether or not it is in a simulation. So goes the famous thought experiment in which a person’s brain is disembodied, suspended in a vat of liquid with its neurons wired to a supercomputer delivering electrical impulses, and is oblivious to set up, as the impulses would be indistinguishable from those that the brain usually receives. They would carry on with their life, having a conscious experience as normal as any other, unaware of the vat or the supercomputer.

Reality is simply what we perceive to be real. Right now as you read this article, some of what you’re seeing is an illusion. Your brain can’t process all of the sensory data it is bombarded with, so it processes what it can and fills in the rest. What you see in your peripheral vision is only what your brain thinks could be there, and yet all of what you see is considered equally real. As Democritus put it, “By convention there are sweet and bitter, hot and cold, by convention there is color; but in truth there are atoms and the void.”

The question of what kind of world we truly live in has always fascinated us. Pop culture is full of films and books in which characters realize their reality is a fabrication, like The Matrix, The Truman Show, and Ender’s Game, to name a few. Today we’ll be looking at Professor Nick Bostrom’s take on it, which is explained in his famous 2003 paper Are You Living In A Computer Simulation?

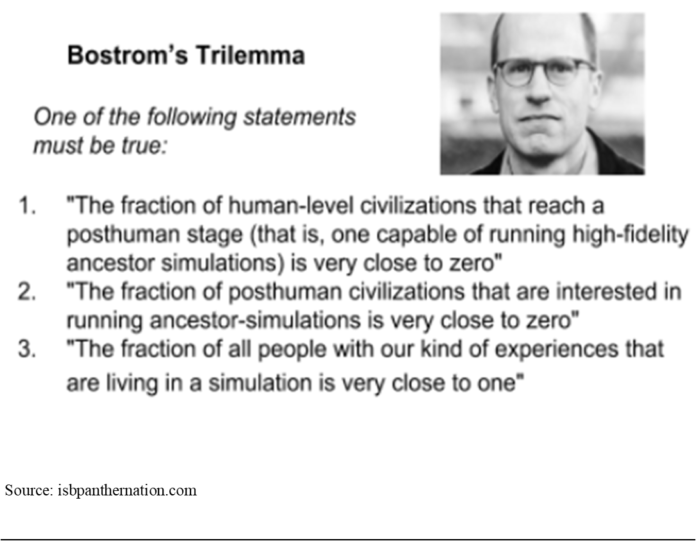

The paper asserts that one or more of these propositions has to be true:

1) the human species will go extinct before reaching a “posthuman” stage

2) any posthuman civilization is unlikely to run a significant amount of simulations of their ancestors, either for lack of desire or because of high costs

3) we are almost certainly living in a computer simulation

A posthuman civilization is simply a civilization far in the future whose inhabitants are beyond what we currently define as human. They are so technologically advanced that they have transcended the human experience. In his book Sapiens, Yuval Noah Harari writes, “Tinkering with our genes won’t necessarily kill us. But we might fiddle with Homo sapiens to such an extent that we would no longer be Homo sapiens… future Dr Frankensteins could therefore create something that will look at us as condescendingly as we look at the Neanderthals.” There have been many science fiction takes on what a civilization like this might look like (for example, the worlds of Matter by Iain M. Banks and Blindsight by Peter Watts) but the truth is, there is a slim chance of it happening at all. There is no reason to think that our species will survive long enough to see posthumanism. Homo sapiens have been around for roughly 200,000 years (which isn’t much compared to other species in our genus, such Homo habilis, who lived for a million years) and with threats like climate change and overpopulation looming on the horizon, things are not looking good for us. It is likely that humans will go extinct before having the computing power to build the kind of simulations Bostrom’s argument presents. If this happens, the argument (that one or more of the propositions is true) will be correct.

Now, say a posthuman civilization is conceived. They have the computational power to create the kind of simulation Bostrom is discussing–an entire world of conscious minds and an environment for them to inhabit. It’s extremely difficult to make an estimate of how much power this would actually take. Discussions about this usually devolve into pure conjecture, but even still, Bostrom provides some interesting takes on how it could be done. “Simulating the entire universe down to the quantum level is obviously infeasible,” he writes, “unless radically new physics is discovered. But in order to get a realistic simulation of the human experience, much less is needed–only whatever is required to ensure that the simulated humans, interacting in normal human ways within their simulated environment, don’t notice any irregularities.” The insides of atoms do not need to be continuously simulated. They can be filled in when needed; if someone looks through an electron microscope, for example. The far reaches of the solar system can have “highly compressed representations.” Another way to save on computational power would be to have a simulation with a smaller group of conscious minds. Bostrom writes, “The rest of humanity would then be zombies or ‘shadow people’–humans simulated only at a level sufficient for the fully simulated people not to notice anything suspicious. It is not clear how much cheaper shadow-people would be to simulate than real people. It is not even obvious that it is possible for an entity to behave indistinguishably from a real human and yet lack conscious experience.” The point isn’t how the posthumans would run their simulations, simply that they can. They would have enough power to run a large number of them while expending only a fraction of their resources. The second proposition simply states that, despite this, they would not.

Why not? If our species, at this moment, became capable of running simulations of our ancestors, we would jump at the chance. Imagine how much easier it would be for historians to understand why certain decisions were made in the past if they could replicate the exact settings in which those decisions were made, and watch real people existing inside of them. (“Real people” as in conscious minds that are just as capable and varied as the minds of people like us. Make no mistake, this is not a Matrix-type situation where minds are transported into a simulation and the bodies are outside of it. These simulated people have no bodies independent of the simulation.) Instead of going to a Renaissance fair, someone interested in that time period could simply build themselves the Renaissance. Wish you had been around for 800’s Al-Andalus? For the Mongol Empire? For Easter Rising? Posthumans would be able build a simulation of any of these times and watch it play out, for their own recreation. Chuck Klosterman writes about the possibility that the world we inhabit was created by a kid in the year 4956 who built a simulation in order to pass the time on a Sunday afternoon, writing, memorably, “…the future is a teenage crackhead who makes shit up as he goes along.”

Bostrom explores two reasons why posthumans wouldn’t run simulations, despite their ability to. The first is that it would be useless for them. The reason we would use a simulation to study history would be to learn things, but what if posthumans have nothing left to learn? Obviously, they will understand the universe in a way we could never dream of. Another reason to run a simulation would be for entertainment–the kid in his garage on a Sunday afternoon, or the Renaissance enthusiast. To counter this, Bostrom writes, “… maybe posthumans regard recreational activities as merely an inefficient way of getting pleasure–which can be obtained much more cheaply by direct stimulation of the brain’s reward centers.” Or, say, posthumans with these human desires for recreation do exist. They simply can’t afford to run a simulation. Just because the civilization as a whole is capable of doing it does not mean every member of the civilization is. NASA could send another man to the moon if they liked, but your next-door neighbor, no matter how much they want to, probably cannot.

This brings us to the third proposition. If the first two are false, meaning that our species did reach a posthuman civilization capable of running simulations and is interested in doing so, that means we are most likely living in a simulation right now. Consider it: an unlimited number of simulations can be created, each of them containing a population of conscious minds. There is only a single reality that exists independently of any simulation. In Elon Musk’s words: “The odds that we’re in a base reality is one in billions.”

One of our species’ biggest questions has always been about the existence of god. This could finally provide a straightforward answer. If we’re living in a simulation, someone must be controlling it. Bostrom writes, “In some ways, the posthumans running a simulation are like gods in relation to the people inhabiting the simulation: the posthumans created the world we see; they are of superior intelligence; they are ‘omnipotent’ in the sense that they can interfere in the workings of our world even in ways that violate its physical laws; and they are ‘omniscient’ in the sense that they can monitor everything that happens.” This brings into question the chances of our simulation being terminated. Could our posthuman manager run out of resources or the desire to continue, and shut down the simulation? Would this be accepted in a posthuman civilization, or would there be ethical restraints on it? Would the minds inside simulations have rights? Or, perhaps the posthuman manager wanted to cut down on computing power by severing only some of the minds and keeping others. Would this result in some kind of judgement day? Would the whore of Babylon ride in on a seven-headed beast proclaiming a virtual Armageddon?

Other than the possibility of termination, living in a simulation would not be different in any meaningful way than living in a base reality. As Bostrom puts it, “… the implications are not all that radical. Our best guide to how our posthuman creators have chosen to set up our world is the standard empirical study of the universe we see.” There would be no real reason to change the way we behave. (In How to Live in a Simulation, author Robin Hanson operates on the assumption that posthumans will run a simulation until they get bored, then eradicate it. Accordingly, his primary piece of advice is to “be entertaining and praiseworthy.” Take that with what you will.)

Bostrom writes, “In the dark forest of our current ignorance, it seems sensible to apportion one’s credence roughly evenly between (1), (2), and (3).” If you are someone particularly concerned with the future of humanity, you might hope for (2) or (3). If you are someone who is disturbed by the idea of living in a simulation, you might wish for (1) or (2). No matter where you stand, it’s difficult not to put faith in the Simulation Argument.