By: Maler Suresh

Source: nytimes.com

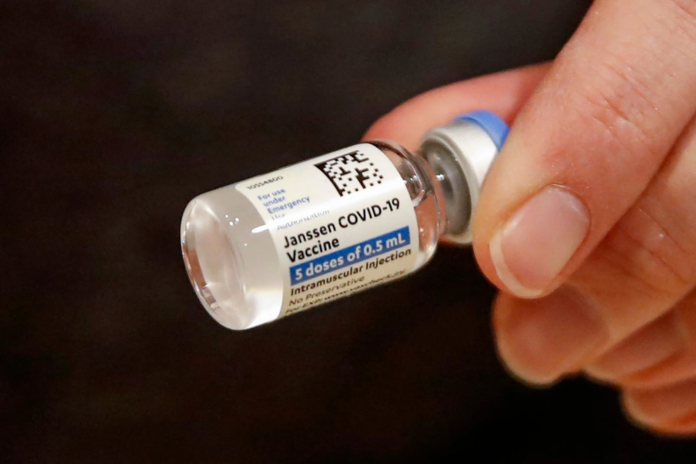

Earlier in April, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recommended a pause on the distribution of the Johnson and Johnson vaccine due to the fact that among the 6.8 million people who had received the vaccine, six women developed blood clots within two weeks, one case of which was fatal. The Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) met again on April 23 and voted to recommend resumption of the vaccine’s use in people age 18 and older with a warning about the rare risk of blood clots, especially in women ages 30-39. Following the recommendation, the CDC and FDA reauthorized distribution of the vaccine. A similar situation occurred in Europe with the AstraZeneca vaccine not a month earlier. In which 15 have developed DVT, or blood clots in vein blood vessels, and 22 have developed clots in the lungs that originated elsewhere and traveled to pulmonary arteries out of the 17 million people who had received the vaccine. Both vaccines are made with adenovirus vectors (viruses that have been modified to harmlessly deliver instructions to the body on how to fight COVID-19.)

The blood clots caused by the vaccines are unique in that they can form even in patients who had low platelet counts in their bloodstream. Additionally, the clots are forming in serious places such as the brain, the lungs, the legs or the abdomen, despite the fact that platelet counts are really low. The symptoms of the blood clots, such as headaches, appear around one-two weeks after the vaccination, far removed from the usual vaccine side effects, and continue to worsen from that point forward.

As for what might be causing these blood clots, the leading hypothesis is that parts of the AstraZeneca vaccine stick to a protein called PF4 that platelets release during the formation of blood clots. These pieces of vaccine and protein can form clumps of molecules that your body sees as foreign invaders. This may lead to a cascade of reactions that cause platelets to turn into dangerous clots. Much more evidence is needed to truly investigate the specifics and viability of this theory.

While sharing this information with the public may initially increase hesitancy in people who still have not received the vaccine and slow roll-out, experts hope that the transparency from companies and public health officials will create a trusting, informed environment for the public and eventually increase confidence in the vaccine.