If you’ve ever stepped foot in the Midwest or Northeast, you know it’s freezing outside. Everywhere you look, there is snow and wind, with temperatures reaching a low of -30 degrees Fahrenheit in the Midwest – and that doesn’t include windchill, which makes it feel like -50 or 60. One of the causes of this is the polar vortex.

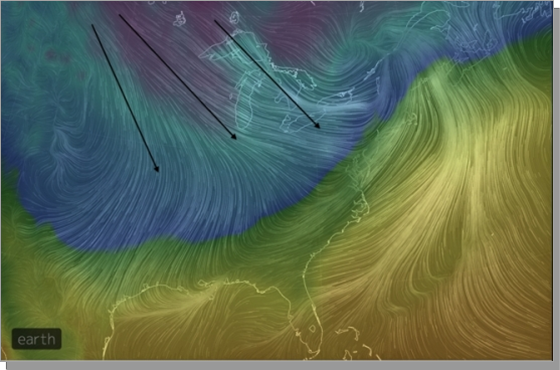

A polar vortex is an area of low pressure in the upper atmosphere that typically has centers near Canada’s Baffin Island and over northeast Siberia. The vortex is strongest in winter, due to an increased temperature contrast between the polar regions and the mid-latitudes, including the United States.

In this case, a large piece of the vortex broke off and was forced south over Ontario and the northern Great Lakes. Instead of cold, Canadian air barely affecting the northern tier of the U.S., then draining off into the north Atlantic Ocean, the Arctic air plunged south into the U.S. When this occurs, the central, southern and eastern U.S. plunge into a deep freeze, with subzero cold over large swaths of the Midwest, interior Northeast and parts of New England. The Arctic outbreak, while dangerously cold, will not persist long as the polar vortex has returned to its center in Baffin Island, Canada.

It is possible that this distortion of the polar vortex could be due to global warming, although it has occurred before. It seems counterintuitive that global warming could cause significant cold snaps like this one, but some research shows that it could. Different types of extreme weather can result from the overall warming of the planet, melting of the Arctic Sea ice, and other events. This includes extreme distortions of the jet stream, which can cause heat waves in summer and sudden cold in winter.

The vortex hit America hard, with 200 million people affected and the impact calculated to be $5 billion. $50 to $100 million was lost by airlines, which cancelled a total of 20,000 flights after the storm began. Further delays were caused by the weather at airports that did not possess de-icing equipment. At O’Hare International Airport in Chicago, the jet fuel and deicing fluids froze. Not included in the total were the insurance industry and government costs for salting roads, overtime and repairs.

Over a dozen deaths were attributed to the cold wave, with dangerous roadway conditions and extreme cold cited as causes. Three Amtrak trains were stranded overnight on January 6, 80 miles west of Chicago, due to ice and snowdrifts on the tracks. Another Amtrak train was stuck near Kalamazoo, Michigan for 8 hours, while going from Detroit to Chicago. Chicago Metra commuter trains reported numerous accidents.

During the cold wave, the strain on the power supply caused 24,000 residents to lose power in Indiana, Illinois, and Missouri. Here in Buffalo, it’s almost like a normal winter.

people need to be smart about the gieclars and global warming: The few plants that live in Antarctica today are hardy hangers-on, growing just a few weeks out of the year and surviving poor soil, lack of rain and very little sunlight. But long ago, some parts of Antarctica were almost lush.New research finds that between about 15 million and 20 million years ago, plant life thrived on the coasts of the southernmost continent. Ancient pollen samples suggest that the landscape was a bit like today’s Chilean Andes: grassy tundra dotted with small trees.This vegetated period peaked during the middle Miocene, when atmospheric carbon dioxide levels were around 400 to 600 parts per million. (Today, driven by fossil fuel use, atmospheric carbon dioxide has climbed to 393 parts per million.)As a result, global temperatures warmed.Antarctica followed suit. During this period, summer temperatures on the continent were 20 degrees Fahrenheit (11 degrees Celsius) warmer than today, researchers reported June 17 in the journal Nature Geoscience. When the planet heats up, the biggest changes are seen toward the poles, study researcher Jung-Eun Lee, a scientist at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory, said in a statement. The southward movement of rain bands made the margins of Antarctica less like a polar desert and more like present-day Iceland. [Ice World: Amazing Glaciers]

Comments are closed.