By Hank Bartholomew

On March 7, 2025, sixty-seven year-old Brad Sigmon was executed by firing squad at Broad River Correctional Institution in Columbia, South Carolina. Sigmon’s method of death was the first instance of an execution by firing squad in fifteen years, and the return of such a particularly brutal form of execution has raised increased controversy over capital punishment and its future in the United States. In the weeks following Sigmon’s death, advocates of an end to capital punishment have pointed to Sigmon’s execution–which is just the latest in a string of experimental and unusual forms of death–as evidence of the increasing cruelty of the death penalty, sparking heated debate over both the legality and morality of capital punishment.

To understand the significance of Sigmon’s execution by firing squad, it’s important to understand the context surrounding its occurrence. Sigmon’s execution was in response to his 2001 crime, in which he violently murdered the parents of Rebecca Barbare, his ex-girlfriend, before attempting to kidnap her. After eleven days on the run from the law, Sigmon was arrested in Gatlinburg, Tennessee, and subsequently brought back to South Carolina and charged for a slew of crimes, including two counts of murder and kidnapping. In July of 2002, Sigmon was brought to trial, where he admitted his guilt and asked for life in prison. Despite Sigmon’s legal team noting his history of drug abuse and good behavior while awaiting sentencing, Sigmon was unanimously sentenced to death on July 20, 2022.

After several years of unsuccessful appeals to the State Supreme Court, Sigmon’s execution was set to May 7, 2025. While waiting for the impending date, Sigmon found himself faced with what he and his legal counsel have described as an impossible choice: his method of death.

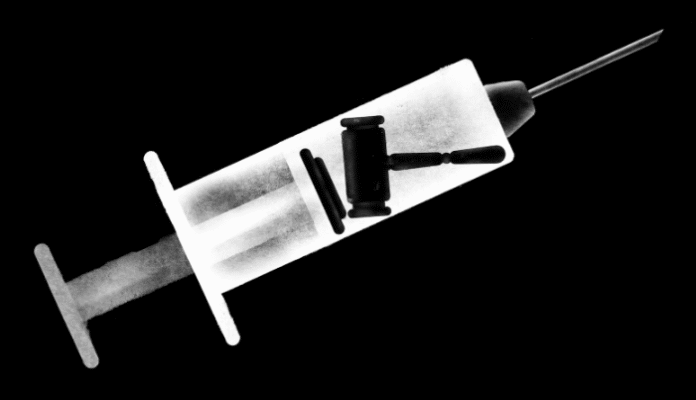

The fact that Sigmon had a choice in his way of execution is a new phenomenon. Within the past few years, several widely-publicized failures of execution due to complications with intravenous injection have led to new, often untested procedures being used to carry out executions. For instance, in 2022, Kenneth Eugene Smith, a prisoner on an Alabama death row, was executed–for the first time in world history–by nitrogen hypoxia, the removal of oxygen from an environment, after a failed intravenous injection. These difficulties with intravenous injections have led several Southern states to introduce and offer new procedures. Sigmon (as well as several of his fellow Columbia death row prisoners) were given three options: the electric chair, lethal injection, or firing squad.

The reasoning behind Sigmon’s choice is largely what is responsible for the public outcry following his death. Sigmon and his lawyer, Gerald “Bo” King, chief of the capital habeas unit in the federal public defender’s office, argued that all three options were inhumane and dehumanizing, with execution by firing squad seeming only slightly preferable. Sigmon has been recorded as saying that he feared an electric chair would be a brutal and extremely painful death, and even made a plea to the South Carolina Supreme Court to postpone his sentence on such grounds, although this appeal was ultimately unsuccessful. Furthermore, Sigmon and his legal team were fearful of the potential for a painful death from lethal injection, citing autopsy reports from other Columbia death row prisoners that came back indicating that these prisoners had not been pronounced dead after twenty minutes, and that one of the prisoners had died with fluids in their lungs, which medical experts suggest may have led to a sensation of drowning in that individual’s final moments. Facing these facts, Sigmon opted for execution by firing squad–but only as a last resort, as he recognized the brutality and violence of such a method. Per the Equal Justice Initiative, executions by firing squad can pulverize bones and organs, leading to excruciating pain, as well as potentially mutilating the body. Prior to the execution, King told the Associated Press that “Brad has no illusions about what being shot will do to his body. He does not wish to inflict that pain on his family, the witnesses, or the execution team. But, given South Carolina’s unnecessary and unconscionable secrecy, Brad is choosing as best he can. . . . Everything about this barbaric, state-sanctioned atrocity – from the choice to the method itself – is abjectly cruel.”

This is the crux of the argument. Sigmon’s legal team–and those who oppose the death penalty nationwide–argue that being forced to choose between three inhumane options of execution constitute cruel and unusual punishment, and thus are a violation of the Eighth Amendment, which promises that for all legal offenders, “excessive bail shall not be required, nor excessive fines imposed, nor cruel and unusual punishments inflicted.” In the eyes of King and many others, being forced to choose between an incredibly painful death, a prolonged death, and death from a method that can be incredibly destructive to the human body–as well as potentially result in brief pain–is no choice at all; all three options are inhumane and without dignity, and thus constitute cruel and unusual punishment.

Without getting too far into the philosophical and legal weeds, it’s important to understand what the standard is for cruel and unusual punishment. Although such standards vary significantly, there are three highly general rules of thumb for identifying if a punishment can be deemed cruel or unusual. First, a punishment is worthy of such a designation if it significantly differs from the punishments of other individuals who have committed similar crimes. As far as this standard is concerned, Sigmon’s team lacks a convincing argument; in South Carolina, execution is not an unusual punishment for homicide.

The second standard is one that lends greater credence to King’s argument. Most legal experts agree that any punishment that is dehumanizing can be classified as cruel and unusual. For example, in 1972 Delaware became the final state to ban the use of stockades or whipping posts, citing the public humiliation associated with such punishment as dehumanizing. An argument can–and likely will–be made that a firing squad, with its connotations of political prisoners and mass executions, may constitute an example of such dehumanizing punishment.

Finally, and perhaps most significantly, a punishment may be deemed cruel or unusual if it inflicts unnecessary and wanton pain. This is where Sigmon’s supporters find their strongest argument. The three methods Sigmon was forced to choose between all involved a degree of pain, be it overstimulation of the nervous system, a sensation of drowning, or the pain of a gunshot wound.

The rebuttal to such a claim is that execution via firing squad (and by electric chair and lethal injection, to a lesser extent) results in immediate death, and thus can not be labeled as inflicting pain. But the truthfulness of such a claim is unclear. Indeed, several attendees of the execution have filed reports that indicate Sigmon’s death was not immediate, and that he may have been in tremendous pain in his final moments. A local reporter, covering the execution for WYFF 4 News, described how after the shots were fired, “His [Sigmon’s] arms flexed. There was something in his midsection that moved. I’m not necessarily going to call them breaths. I don’t really know,” and that in the seconds that followed the shots being fired, Sigmon’s body continued to move. King, also watching the execution live, called the procedure “horrifying and violent,” noting how after the shots had been fired, Sigmon’s arm tensed up and shook, “as if he was trying to break free from the restraints.” Approximately a minute later, a medical professional entered the chamber and declared Sigmon dead after a ninety-second examination.

The brutality of execution by firing squad, as well as Sigmon’s lack of a humane, non-painful way of death, have led to widespread outcry from human rights advocates. Yet Brad Sigmon’s execution has raised more than just the question of if capital punishment is acceptable; it has also raised questions over the ability of an individual to change over time, and how the law should accommodate such changes. King, during a press conference prior to the execution, pointed to Sigmon’s behavior in prison as evidence that he was a changed man. While in prison, Sigmon became deeply religious, serving as an informal chapel to other prisoners. Furthermore, Sigmon has also fully admitted to and apologized for his crimes, and still maintains contact with family members and his children. King, in a statement, added that Brad admitted his guilt at trial and shared his deep grief for his crimes with his jury and, in the years since, with everyone who knew him.” In his final words, Sigmon even proclaimed, “I want my closing statement to be one of love and a calling to [his] fellow Christians to end the death penalty.” Whether such behavior can counteract his misdeeds twenty-four years ago is unclear. But in the eyes of many, the Brad Sigmon that was sentenced to death was not the same Brad Sigmon that was executed. Sigmon has–or at least appeared to have–grown morally and theologically during his time in prison. Should there not be a noting of that fact within the legal system?

As of this writing, there are still twenty-eight individuals sitting on the South Carolina death row. Their fates–as well as the fates of others just like them in other states–hangs in the balance, partially dependent on the fallout of the national outcry from Sigmon’s death. With the current presidential administration generally deferring to the states in matters of criminal justice, execution by firing squad may continue to play a large role in capital punishment. Already, five states–Idaho, Missisip, Oklahoma, Utah, and, of course, South Carolina–allow for execution by firing squad. Brad Sigmon’s execution opens the door for more to join them.

The central question here is not necessarily the morality of the death penalty; rather, it is the ethics of carrying out such a punishment. Capital punishment is a hotly debated issue that likely will continue to split Americans in the years to come. But what we should all be able to agree on is that if such a practice is continued, those who are subject to it must be treated with decency, humanity, and respect. By all accounts, it appears Brad Sigmon was not. Perhaps Gerald King summarized it best: “There is no justice here.”

Brad Sigmon’s execution marks a potential turning point for capital punishment in America. The United States has revived an old practice–deemed harsh and unnecessary several years ago–and revitalized it. From here, there are two options: return to our past traditions regarding the death penalty, using whatever procedures necessary to enact it, or continue our gradual reform and rectification of capital punishment, with Brad Sigmon’s death a deviation–and teaching point–on the road to ending the death penalty. The choice lies in us–all of us.