By Pen Fang

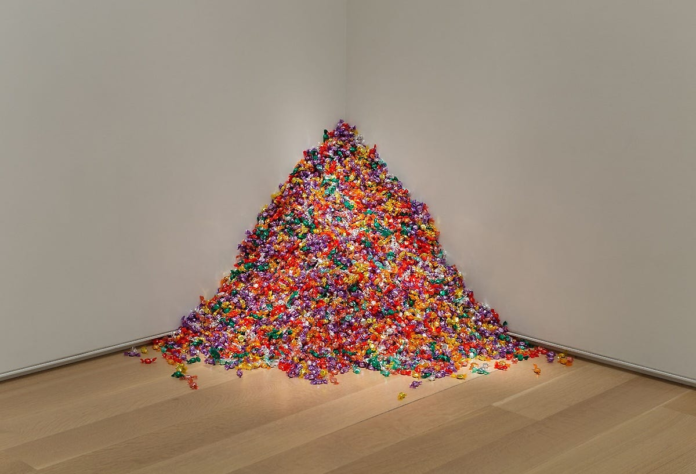

Perhaps you’ve heard of this work of art: a pile of candy in the corner of the room, set to an ideal weight of 175 pounds. The endless supply slowly disappearing as guests take pieces throughout the day.

Untitled (Portrait of Ross in L.A.) is one of twenty “candy works” — an iconic series of the works of artist Felix Gonzalez-Torres. Fifteen of these “candy works” have ideal weights — ranging from the average weight of an adult man to the average weight of an adult woman to the average weight of two adult men.

Each candy work is unique, and may differ based on the interpretation of the owner. It is an integral part of the candy works that it viewers must be permitted to choose to take individual pieces of candy from the work. The candies may or may not be replenished at any time. Portrait of Ross in L.A. specifically is interpreted to be about Gonzlez-Torres’s partner Ross Laycock, who died of AIDS-related complications in 1991 — the same year Portrait of Ross in L.A. was created. Laycock’s weight was also 175 pounds. In taking candies from the work, visitors become a part of Laycock’s destruction.

In fact, it is impossible to separate the impact of the HIV/AIDS epidemic and queer identity on Gonzalez-Torres’s work. During a time when queer art — and especially HIV positive gay male artists — were being targeted for censorship, his use of common, everyday objects like candy and paper made it so you couldn’t censor his art without appearing ridiculous. Furthermore, the ability of his pieces to be easily replicated made his pieces indestructible.

Art collector Nancy Magoon says, “I would describe him as someone who dared to make us think about what he meant by his art.”

Gonzalez-Torres was involved in a variety of social and political causes. One of his works is Forbidden Colors. The piece consists of, as the title suggests, four squares of color: green, red, black, and white.

“It is a fact people are discriminated against for being HIV positive. It is a fact the majority of the Nazi industrialists retained their wealth after the war. It is a fact the night belongs to Michelob and Coke is real. It is a fact the color of your skin matters. It is a fact Crazy Eddie’s prices are insane. It is a fact that four colors—red, black, green and white—placed next to each other in any form are strictly forbidden by the Israeli army in the occupied Palestinian territories.” This color combination can cause an arrest, a beating, a curfew, a shooting, or a news photograph,” he wrote about the piece. “Yet it is a fact that these forbidden colors, presented as a solitary act of consciousness here in Soho, will not precipitate a similar reaction.

“From the first moment of encounter, the four color canvases in this room will ‘speak’ to everyone. Some will define them as an exercise in color theory, or some sort of abstraction. Some as four boring rectangular canvases hanging on the wall. A few experts will interpret them as yet another minimalist ecstasy. Now that you’ve read this text, I hope for a different message.”

“[Gonzalez-Torres] reintroduced what has been sublimated in much Modernist art—desire, loss, vulnerability, and anger—with a potent but quiet poignancy through texts inscribed on giveaway paper sheets and subtitles appended to “untitled” works,” the Guggenheim describes. “Free for the taking and replaceable, Gonzalez-Torres’s perpetually shrinking and swelling sculptures defy the macho solidity of Minimalist form, while playfully expanding upon the seriality of the genre and the quotidian nature of its materials.”

I think the candy works are also such a poignant way of representing what art means to human existence. The viewer takes a piece of something created by another human, laced with meaning that perhaps cannot be fully comprehended. The viewer then consumes that something, and it becomes a part of them. It transforms them. Perhaps it even sustains them.

Untitled (Perfect Lovers), one of Gonzalez-Torres’s most renowned and heartbreaking pieces, consists of two identical clocks, hung side-by-side in contact with each other. The clocks start in perfect synchronization, but due to natural variation throughout the course of day, one clock always ends up falling behind.

The piece has ambiguous meaning but has been interpreted to be a commentary on Laycock’s battle with AIDS and a memorialization of their love. Gonzalez-Torres has also described it as, “the scariest thing I have ever done.”

“Don’t be afraid of the clocks, they are our time, the time has been so generous to us,” Gonzalez-Torres wrote in a letter to Laycock with a sketch of the piece. “We imprinted time with the sweet taste of victory. We conquered fate by meeting at a certain time in a certain space. We are a product of the time, therefore we give back credit were it is due: time. We are synchronized, now forever. I love you.”

Gonzalez-Torres also has a series of portraits challenging the standards of portraiture. He captures the human essence and its mutability not through depictions of faces and bodies, but rather through experience. Each of his portraits is made up of horizontal lines of text — listing people, places, objects, events, and dates in random order — on the wall just below where the wall meets the ceiling.

In creating these portraits, Gonzalez-Torres asked the subject about formative moments, then merged these personal histories with larger historical events, History with a capital H.

“We are not what we think we are, but rather a compilation of texts. A compilation of histories, past, present, and future, always, always shifting, adding, subtracting, gaining,” he wrote in a letter. “These portraits are an attempt at dealing with the theoretical and limited aspects of portraiture. We are as much a product of the invention of TV as we are the product of our parents, and domestic environments, historical events and accidents, and the social forces that have shaped that so-called ‘public’ life.”

Helen Molesworth, art curator, explains, “When you look at a Felix Gonzalez-Torres portrait, one of the things you’re looking at is a really full awareness of our brief time here on Earth, and the role art has always played in commemorating, acknowledging our time here as much as it prepares us for the time that lies ahead of us.”

“And it’s this going between, of public and private, of historical and personal, that really gives these portraits their extraordinary resonance.”

“Felix’s portraits allow us to experience not only who we are, but how we change. And how we change in relationship how the world is changing too.”

I had the opportunity of seeing one of his pieces — namely, Untitled (Double Portrait) — at the Buffalo AKG Art-Museum (formerly the Albright-Knox Art Gallery). This specific portrait consists of a stack of hundreds of papers, each decorated with a pair of gold rings just barely touching at their outermost edges. The piece “personif[ies] two individuals joined in intimacy, support, and love. This relationship is extended as visitors are encouraged to take a sheet of paper home with them.” The museum even provides rubber bands to help those taking a sheet of paper. The description of the medium reads: “Offset print on paper (endless supply).”

I have a sheet of Double Portrait in my room, taken on the day I visited the AKG Museum. In many ways, this single sheet the size of a small poster, decorated with two just-touching gold rings, for me, represents the ever-changing meaning of art due to context. The hope and inspiration and loss in this work echoes across each sheet taken by each visitor, meaning something unique to each person. And furthermore, this piece is the physicality of art’s eternal legacy: Gonzalez-Torres may no longer be with us but this part of his art and him, by extension, is physically with me. He’s physically existing in this space with me beyond his death.

Gonzalez-Torres’s work is simple yet brilliant. His experimentation blurs the lines between artist and viewer. He dares to bend the boundaries of art and storytelling and leave us with something that can touch us so deeply and fundamentally. He transforms what art is and what art can do.