By Philip Baillargeon

More Americans than ever demonstrate a significant distrust in their federal government, and part of the reason why there is so much tension between citizens and their representatives is it takes weeks for any remotely contentious bill to pass. If you’re remotely familiar with Senate politics in the last decade, you’re likely familiar with the expanded use of the filibuster, which allows for any bill with the support of less than 60 Senators supporting it can enter “infinite debate purgatory”. A bill on universal background checks for firearm purchases, the expansion of voting rights, or anti-discrimination measures to protect transgender individuals can all be filibustered, ending a bill with majority support’s life without holding a single vote. What you may be less familiar with is budget reconciliation, the antithesis of the filibuster. However, budget reconciliation is the cure to the filibuster like chemotherapy is the cure to cancer; the process is slow, arduous, painful, and may still be largely unsuccessful for taking action on urgent issues.

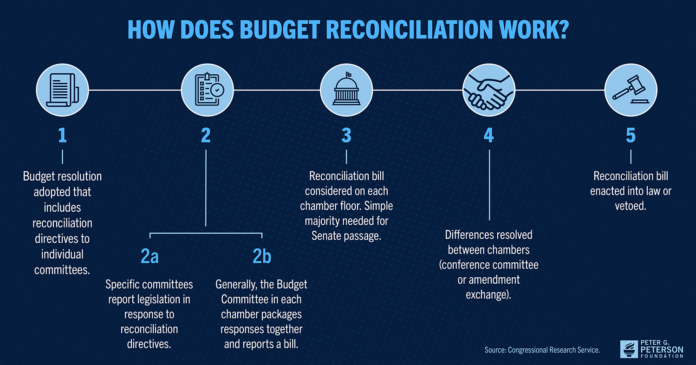

In 1974, the Congressional Budget Act created a pathway for a simple majority to pass certain types of legislation to circumvent the gridlock of the US Senate. It’s been increasingly more popular in the 21st century, being used to pass tax cuts by Presidents Bush and Trump as well as portions of the Affordable Care Act under President Obama. The only catch is, to pass a bill through budget reconciliation, the sponsors of the bill must prove that the content of the bill is related to a change in taxes and spending. This is the “Byrd rule”, named after Senator Robert Byrd, and it is meant to prohibit unrelated measures from being snuck into massive budget bills. The Democrats’ COVID relief bill had some measures, such as an increase in the minimum wage to $15, struck from the bill because the Senate Parliamentarian, who determines what is relevant to the budget, struck down these portions of the bill.

Technically, however, the Senate majority leader could just fire the Senate Parliamentarian and replace them with someone who agreed with their views on what is appropriate to pass through this procedure. Also, since Vice President Harris is the Presiding Officer of the Senate, she can opt to overrule the Senate Parliamentarian. This hasn’t been done since 1975, but it is a legal course of action to take.

So, budget reconciliation lets a majority circumvent the 60 vote requirement if they are passing legislation relevant to taxation and spending, but there are many ways to circumvent these requirements. Why would a Senate majority ever try to pass legislation normally ever again?

Budget reconciliation is slow. Very slow. Democrats have been trying to pass the most recent COVID relief bill since late January, moving as fast as they possibly can, and they still haven’t been able to force a vote on this bill until early March. This is because the normal process of running a bill through committee before it is passed has been elongated, since every portion of the bill must be approved according to rules regarding budgeting bills (and this particular bill is over 600 pages long). There are many more snags along the way, like the provision allowing Senator Ron Johnson to demand the entire bill be read in full on the Senate floor, that can also slow the process.

After the passage of this bill, the focus of the Senate will likely turn to voting rights, as the For the People Act (H.R. 1) seems certain to have a vote in the coming weeks. This is a bill that cannot be passed through budget reconciliation, running the risk of killing a highly popular piece of legislation through the filibuster. It would take the entire Democratic caucus to eliminate the filibuster, which is unlikely to happen since Senators Manchin and Sinema seem highly opposed to sacking this parliamentary procedure. While the filibuster remains, get used to budget reconciliation; this slow, archaic process is the only way bills get passed in the modern Senate.